20 years of RISTEX

Dialogue #1

YOSHIKAWA Hiroyuki X KOBAYASHI Tadashi

The concept of 社会技術 (shakai-gijutsu; S&T for Society) which RISTEX advocates, was scrutinized and shaped during the year 2000 by the Study Group on the Promotion of R&D of S&T for Society established in the then Science and Technology Agency. YOSHIKAWA Hiroyuki served as its chairperson, and applied his expertise in design theory/engineering to S&T in general to expand the potential of academic research in providing solutions to social issues by the use of scientific knowledge, expressing such a conduct 社会技術. To this day he continues to be a key figure in 社会技術, for articulating its theoretical aspects and advocating its importance. He generously accepted to take part in the first session of the dialogue series, to look back on the 20 years of 社会技術.

YOSHIKAWA Hiroyuki

Served as the president of the University of Tokyo, president of the Science Council of Japan, president of the International Council for Science (ICSU), and Director-General of the Center for R&D Strategy (CRDS), JST. Currently the president of the International Professional University of Technology in Tokyo/Osaka and a professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo. Major publications include: Design Methodology for Research and Development StrategyI, CRDS, JST, 2012; "General Design Theory and a CAD System," Proceedings of IFIP Working Group 5.2-5.3, 1981; and General Design Theory, 2021 (in Japanese. The English version will be published in 2023).

Conceptualization of 社会技術and Its Background

KOBAYASHI Tadashi (KT): It has been 20 years since the establishment of RISTEX (System), the predecessor of current RISTEX. I want to start our conversation with the term 社会技術 in the Japanese name of this organization. If we were to translate this term literally in English it would be something like 'society's technology,' which is very different from the official English name, the Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society. It seems obvious that the term 'Science and Technology for Society' derives from the Budapest Declaration in 1999.

YOSHIKAWA Hiroyuki (YH): I was invited to speak at the opening session of the Budapest Conference*1 and gave a talk about how scientific knowledge should be 'used,' from the perspectives of my expertise in design engineering. The Budapest Declaration you mentioned was put together and announced at the end of this conference, and it was titled "Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge." In this phrase, the term 'use' had a significant meaning.

KT: Then you were serving as the president of the Science Council of Japan (SCJ), which is a huge responsibility, and on top of that you became the president of the International Council for Science (ICSU).*2

YH: Yes. Back then, the ICSU consisted mainly of basic scientists and engineers were mostly observers. However, Bruce Alberts, then president of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) was thinking ahead about the future roles of the ICSU. He approached me and said that the ICSU needed to engage more deeply with society, that science was mostly concerned with analysis and was not seriously considering how its knowledge could be applied to society, and that approaches and logics developed in the field of engineering would become increasingly more important in future. And he asked me to help him realize such future of the ICSU. At the time I was very busy due to the administrative reform in Japan as the president of the SCJ, but in the early summer of 1999, I became one of the candidates for the president of the ICSU and was elected at a meeting held in Egypt in September. I think it appeared rather odd to the circle of scientists in Japan that someone with an engineering background like me was welcomed in the ICSU, but international academia was already problematizing the dichotomy between science and engineering.

KT: I see. Unlike the term 科学技術 (kagaku-gijutsu) in Japanese, literally meaning 'science-technology' which imply certain vagueness in distinction between the two, the English term 'science and technology' treats them as separate entities linguistically. But in reality, academics were becoming more aware of the importance of bridging them by the 'use' of knowledge in order to address social issues.

YH: While I was the president at the ICSU, we consolidated what were called the ICSU family, 20 or so specialized committees each targeting different issues, into eight committees. It was very challenging because each had different interests, but we persuaded them over three days at a plenary meeting, convincing them that society needed us to work with more comprehensive frameworks. The eight committees emerged then later became the foundation of the Future Earth*3 initiative.

KT: So that is how different disciplines started to work together to deal with global-scale problems.

YH: Yes, and also, there was a clear motivation in academia to bring about a new trend in science, that is, to position 'environment' as a subject of basic science. Jane Lubchenco, who later become the administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), was among such advocates. She claimed that scientists should be able to express their opinions freely as they have autonomy regardless of their affiliation.

KT: She coined the term the 'social contract for science' as I recall.

YH: Yes. Scientists claim their autonomy and conduct whatever the research they want, but many of their research activities are publicly funded. Then, why aren't they challenging the grave problems that humanity is facing? Not many researchers seem to be directing their intellectual curiosity to ethical problems, but is that acceptable? Shouldn't basic research include the consideration of how science could be used and the development of science desirable for society? - she raised such questions, initially in the greeting speech as the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), which was later published as an article in Science.*4 This had a tremendous impact. Incidentally, she became the president of ICSU after me, so I had a privilege of working with her for a year and a half. I recall her as a warm-hearted person.

KT: So internationally, there was a growing awareness of the importance of using academic knowledge for the benefit of society. Meanwhile in Japan, the Study Group on the Promotion of R&D of S&T for Society was set up in 2000. The group consisted of prestigious members with you as the chairperson.

YH: It was remarkable and left a strong impression. Discussions we had were incredibly fruitful.

KT: Its report defines 社会技術 as follows: "there is a need to bring together technical knowledge mainly of natural sciences and knowledge of social sciences and humanities that analyze the nature and behavior of individuals and social groups, in an attempt to harmonize S&T with society, which includes the challenge of formulating new relationships between S&T and humans/societies. Technology (as an application of knowledge) that synthesizes knowledge from multiple disciplines of natural sciences and social sciences and humanities to construct new social systems are regarded as 社会技術." What is described here 20 years ago still holds today. As it happened, the 6th STI Basic Plan was launched this year (FY2021), and it uses the expression 総合知sogo-chi (convergence of knowledge). What it seems to refer to is practically the same as what were discussed in the Study Group then. That makes us realize how sharp the Group's visions were, and also wonder how we should accept that we are still stuck with the same problems today.

YH: We can interpret it as our framework finally gaining certain public legitimacy. At the time of the Study Group, there was a succession of nuclear accidents*5 and thus nuclear research was under heavy criticism. So, there was a need to think of a scenario for the betterment of future by analyzing the situation as carefully and objectively as possible. I suggested that we needed to create a new discipline in which we could contemplate why such incidents occur, and expand the discussion to include the considerations of various other problems of the contemporary society.

KT: The definitions of 社会技術 and 文理融合 (SSH integration) seemed to vary considerably among academics.

YH: 社会技術 has been interpreted mainly in two ways. To some scholars it meant establishing a new discipline to respond to society's various needs, but my interpretation was that it aimed to use knowledge produced in basic research to solve social issues. Thus, researchers who possess autonomy would and should direct their current curiosity to global and large-scale social problems which require interdisciplinary approaches, and such should be the responsibility of today's academia. Natural science can be considered to have corresponding 'technology' which is its application. Likewise, I think there should be 'technologies' which are the applications of various findings in social sciences that solve social issues or that improves policymaking. That is what I consider as 社会技術. Then, despite the difficulty in integrating natural and social sciences, there would be a common language between the two that expresses how and why knowledge is used, which may enable the integration.

KT: That's fascinating. So, the desire to transform Japanese academia was embedded in your concept of 社会技術.

*1 An international scientific conference held in Budapest, Hungary, from June 26 to July 1, 1999, that was cosponsored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Council for Science (ICSU). The conference adopted the Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge (Budapest Declaration).

*2 A non-profit international academic institution established in 1931. It promotes international cooperation in S&T and provides advice to governments and society on S&T related issues. In 2018, it merged with the International Social Science Council (ISSC) to become the International Science Council (ISC).

*3 An international research network established in 2015. It aims to realize a sustainable society through research and innovation while collaborating with society.

*4 Jane Lubchenco "Entering the Century of the Environment: A New Social Contract for Science" SCIENCE Vol 279: 5350, 1998.

*5 In March 1997, a fire broke out at a reprocessing facility of the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation, and 37 people were exposed to radiation. In September 1999, a criticality accident occurred at JCO's nuclear fuel processing facility, resulting in two deaths from radiation exposure. The Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute, which was responsible for research on nuclear energy at that time, was dissolved in 2005 and became the Japan Atomic Energy Agency.

社会技術 and Functionality as a Common Language

Symposium "The 10 years and the Future —10 Years after Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge: Science in Society and Science for Society—" 2009. As Director-General of CRDS, JST

KT: I understand that is how the 'use of knowledge' became a global topic of interest at the turn of the century. There was an increasing international awareness of the need to deal with global environmental issues, and this prompted the conceptualization of 社会技術 in Japan, which materialized in RISTEX. It was one unique form of response Japan has made.

YH: Yes, I think it stemmed from the feeling of responsibility to make a real change.

KT: Regarding how to pursue research in 社会技術, "Basic Ideas About Research System" section of the report describes top-down, bottom-up and interactive communication between the two as the 3 approaches to promote research. As a top-down approach, RISTEX initially set up Mission Programs, in which appointed researchers conducted in-house research on given topics. However, after the organizational restructuring, its focus has shifted to the funding of research in 社会技術. Regarding the bottom-up approach, the report describes how surveys and hearings should be conducted widely to gather voices of citizens and experts, of which analysis serves as the foundation for a new funding scheme. Social issue surveys are still conducted today as the first step of establishing a new program.

YH: Supporting research on 社会技術 can be extremely difficult. For example, it is not easy for young researchers to write academic papers as it is not a simple conduct-experiments-and-collect-data procedure.

KT: That's one of the persisting problems. There always are ambitious young researchers who are willing to commit themselves to social issues but doing so is less likely to result in academic papers that receive recognition. Thus 社会技術 is exciting but a risky option in terms of the academic career path.

YH: There are so few employment options for those engaged in this field, except for those in tenure positions. Not having an ecosystem to comprehensively nurture academia from regional to national levels is a serious problem. Regarding research funding which are either national, industrial, or from other resources, there are more budgets from charities in the UK and the US compared to Japan, and this is where we see some cases of development of new disciplines.

KT: I agree. Also, there is a growing interest in forecasting and discussing, by integrating sciences and arts, issues related to social applications of AI and biotech. For a decade or so, research centers open to people with diverse backgrounds have been emerging around the world. Meanwhile in Japan, there hardly are such cross-sectoral research centers even within universities. RISTEX functions as such to some extent but I think it is too small to be impactful.

YH: I have high hopes for RISTEX, but there should be more social support. As we are trying to bring in more S&T in society, I think it is our duty to prepare a discipline that integrates natural sciences and SSH from early stages of conceptualization. As there are people from the corporate sector who agree with us, it seems feasible but the problem lies in the lack of incentives in the academia.

KT: I understand that design engineering which is your specialty is exactly the discipline that aims to achieve that, and in fact, I believe that is the objective of engineering. Japan though has long been used to being good at adopting and improving models and standards developed in other countries, and has not really tried to come up with new standards for novel ways to solve problems.

YH: I think Japan is inexperienced in thinking in abstract terms when solving problems, as it is more accustomed to approaches based on physical objects. However, I think this is where design engineering truly exhibits its potential. In General Design Theory published in 2021, I suggested to look at various objects from the perspective of their 'functions' before considering materialistic and existential aspects. By theorizing functionality, we realize that when we make things we are producing artefacts with different types of functions but they share the fact that they all have functions. When things are converted into physical things, they become specific artefacts but at the root, they all have the common language of functionality, and there is no division between natural sciences and SSH in such a language.

KT: I see. By focusing on functionality, we are free from the materialistic conditions of what exhibits the function and thus no longer bound to individual artefacts. So, if we were to focus on 'calculating' as a function, it doesn't matter whether it is delivered by proteins or silicon. Such an approach seems useful for R&D in S&T for Society.

Pursuit of Intellectual Curiosity and Research Rooted in Society

A scene from the online dialogue

KT: What do you think would be typical examples of S&T for Society (STfS)?

YH: After the Great East Japan Earthquake, a sociologist NITAGAI Kamon conducted a survey in the affected areas, but the local people were reluctant to talk about the disaster. Then he noticed that they relaxed and spoke spontaneously whilst they were having foot baths provided by volunteers. So, he wrote down and analyzed the words they uttered. This I think is a model approach. Also, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic would be a good example of problems to be tackled with STfS, as people's mobility and globalism are at the root of this issue. Perhaps it is possible for economists to lead R&D of STfS to devise new economic policies that would not accelerate further infection, for example. This would be a very timely challenge of STfS today.

As RISTEX has accumulated experiences of tackling complex social issues for 20 years, I think analyzing these and disseminating prototypes of research useful to society would expand the recognition of RISTEX's unique values. Communicating across R&D projects and programs is essential and so is archiving the research activities and achievements to accumulate and pass on knowledges, especially to avoid the findings from previous projects becoming forgotten or lost during the process of official communication among affiliated ministries and agencies.

KT: I agree. We should try to prevent new projects starting from scratch each year because we lose contact with completed projects and fail to pass on their knowledge to new ones.

As we are nearing the end of this conversation, I would like to ask you for a message to those who are willing to engage in STfS. You once wrote in your book that researchers should be able to conduct curiosity-driven research freely, but they are somehow affected by the age they live in. Yet out emerge some researchers who contemplate what meanings their research may have to society, and that is the most desirable development of research.

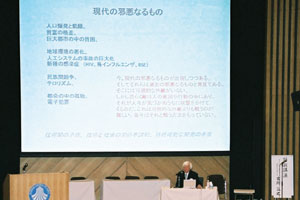

YH: Yes. I once asked the audience "what is curiosity?" in an international conference. They all laughed, as they assumed that it was not something that needed a definition. However, we should remember that many centuries ago, people had curiosity about unknown substances and movements and thus tried to find out what those were. Then, is it not natural for us to be curious about what would happen to the future of the earth? Contemporary malice such as environmental damage, population problems and warfare must be the subjects of our utmost curiosity - I remember serious academic discussions stemming from such conversations. Not because you are asked to, but because you are curious and want to pursue should be the way research is conducted. In many cases, such an idealistic pursuit doesn't fit into existing research frameworks, but I want the researchers to keep trying. Such research must be literally ideological, and the researcher should sincerely wish to make a contribution to society through academic activities. I believe that is how future academia emerges and how academic contributions to the betterment of society is realized. Once knowledge enters academia it is passed on to the next generation through education. Therefore, we seriously need to think how to realize such research. Of course it is important to write papers and secure academic positions, but I hope future researchers can conduct good research, with a free will, pursue intellectual curiosity and contemplate what they seek to understand.

KT: Thank you so much for sharing such meaningful and precious words.

(at Tokyo/online, December 14, 2021)

| 20 Years of RISTEX / S&T for Society TOP >>> |  |