Various Aspects of Development

Normal Development of Fetus and Infant

Recent imaging technology such as 3-D ultrasound movies have enabled observation of the various kinds of fetal movements in the womb after several weeks of gestation, and reveals the possibility of fetus learning in the womb [1]. Vries et al. [2] reported that fetal motility started from the early state of “just discern movements (7.5 weeks)” to the later state of “sucking and swallow (12.5 – 14.5 weeks)” through “startle, general movements, hiccup, isolated arm movements, isolated leg movements, head retroflexion, head rotation, hand/face contact, breathing movements, jaw opening, stretch, head anteflexion, and yawn.” Campbell [3] also reported that the eyes of the fetus open around 26 weeks of gestation and that the fetus often touches its face with its hands during embryonic weeks 24 and 27.

Regarding the fetal development of sense, touch is the first to develop and then other senses such as taste, auditory, and vision start to develop. Chamberlain stated as follows: just before 8 weeks gestational age, the first sensitivity to touch manifests in a set of protective movements to avoid a mere hair stroke on the cheek. From this early date, experiments with a hair stroke on various parts of the embryonic body show that skin sensitivity quickly extends to the genital area (10 weeks), palms (11 weeks), and soles (12 weeks). These areas of first sensitivity are the ones which will have the greatest number and variety of sensory receptors in adults. By 17 weeks, all parts of the abdomen and buttocks are sensitive. Skin is marvelously complex, containing a hundred varieties of cells which seem especially sensitive to heat, cold, pressure and pain. By 32 weeks, nearly every part of the body is sensitive to the same light stroke of a single hair. Both hearing and vision start about 18 weeks after gestation and develop to complete their perception at around 25 weeks [5].

Moreover, it is reported that visual stimulation from the outside of the maternal body can activate the fetal brain [6]. Fig. 1 shows the emergence of fetal movements with the development of fetal senses reflecting the above knowledge.

Fig. 1 Emergence of fetal movements with the development of fetal senses

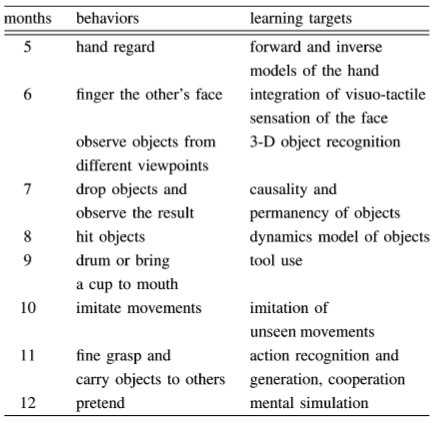

After birth, infants are supposed to gradually develop body representation, categories for graspable objects, capability of mental simulation of actions, and so on through their learning processes. For example, hand regard at the fifth month means learning of the forward and inverse models of the hand. Table I shows typical behaviors and their corresponding targets to learn.

Table 1 Infant Development and Learning Targets

Thus, human fetuses and infants expose cognitive developmental process with remarkable vigor. However, the early cognitive development of the first year after the birth is difficult to visualize since the imaging technology applicable to this age is still very limited, and the following points are suggested.

- We cannot derive the infants’ brain structure and functions from the adults’ ones, nor should do it [7], [8], [9].

- Brain regions for function development and function maintenance are not the same. During early language development, damage of the region in the right hemisphere is much more serious than that of the left [10].

- The attention mechanism develops from the bottom-up one such as visual saliency map to the top-down one needed to accomplish the specified task, and the related brain regions shift from posterior to anterior ones [11].

- Even though the appearances of the performances look similar, their neural structures might be different. Generally, the shift from subcortical to cortical areas is observed from a macroscopic viewpoint. The brain region active for RJA (responding to joint attention) is the same as the region of general attention (the left parietal lobe), but that for IJA (the ability to initiate joint attention) includes the prefrontal area and close to the area for language [11], [12].

Development From a Viewpoint of Synthetic Approaches

Here, we briefly review the facets of development in the survey by Lungarella et al. [13] from viewpoints of external observation, internal structure, its infrastructure, and social structure, especially focusing on the underlying mechanisms in different forms. Fig. 2 summarizes the various aspects of the development according to this review.

From the observation of the behaviors, the developmental process of infants can be regarded as one than is not centrally controlled, but instead a distributed and self-organized process. During the developmental stage, the later structure is constructed on top of the former structure that is a neither complete nor efficient behavior representation. This is one of the biggest differences from the artificial systems [13]. Ecological constraints of infants are not always handicaps but can also serve to promote the development. The intrinsic tendency of co-ordination or pattern formation between brain, body and environment is often referred to as entrainment, or intrinsic dynamics [14]. Self-exploration plays an important role in infancy, in that infants’ “sense of the bodily self” to some extent emerges from a systematic exploration of the perceptual consequences of their self-produced actions [15], [16].

The consequence of active exploration and interaction with the environment is regarded as perceptual categorization and concept formation in developmental psychology. Sense and some sort of perception are processed independent of motion, but perceptual categorization depends on the interaction between sensory and motor systems. In the self-organization, some processes are regulated by neuromodulators that relates to value or synaptic plasticity, and there is a study to predict this kind of interaction from the computational model of meta-learning [17].

Macroscopically, the quality of involvement with caregiver or others promotes the infants’ autonomy, adaptability, and sociality. Scaffolding by a caregiver plays an important role in cognitive, social, and skill development. Infants have “sensitive periods” to caregivers’ responses, and the caregivers regulate their responses to the infants.

Fig. 2 Various aspects of the development from viewpoints of external observation, internal structure, its infrastructure, and social structure