- JST Home

- /

- Strategic Basic Research Programs

- /

ERATO

ERATO- /

- Research Area/Projects/

- Completed/

- SEKIGUCHI Biomatrix Signaling

SEKIGUCHI Biomatrix Signaling

Research Director: Kiyotoshi Sekiguchi

(Professor, Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University)

Research Term: 2000-2005

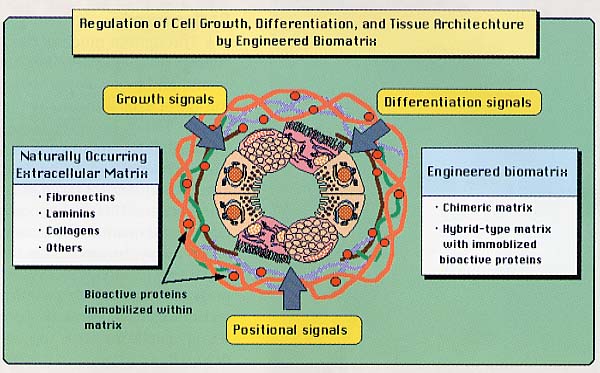

Perhaps the most powerful and long-lasting image in biology is that the basic component of living organisms is the cell. The region between cells has generally been ignored as only a vast scaffold surrounded by an inert fluid that is simply needed to hold cells together into a structural whole. This outdated view is rapidly changing.

The reason for this change is that along with ever-better observational technology and experimental techniques, the intercellular region – the extracellular matrix – has been shown to be not only far more complex than earlier imagined, but that many chemical processes occur there that allow the cells to live and grow, undergo differentiation, find their proper location, and even undergo appatosis. Cells cannot exist without this region. In a way, the intercellular region provides a holistic whole to any multicellular organism.

As a very simple view, organisms are made up of two types of basic structures: one is the epithelium, a sheet of cells that covers the outer surface of any organism as well as that of internal organs; the other is connective tissues that underlie the epithelium and provide the mechanical strength of tissues/organs. These two structures are separated by a special type of extracellular matrix, called the basement membrane. The basement membrane is thus the direct environment or supporting structure for epithelial cells and is considered to play a critical role in the regulation of the growth and differentiation of epithelial cells.

The importance of the basement membrane has been highlighted by recent progress in genome analyses of worms (C. elegans) and flies (Drosophila). Among the many kinds of molecules that form the extracellular matrices, those of the basement membrane are consistently present in these organisms, although those forming connective tissues are not. Thus, the basement membrane appears to be the most primordial form of extracellular matrix prerequisite for the evolution of multicellular organisms.

Epithelial cells adhere to the basement membrane through receptors on the cell surface, which bind to the constituents of the basement membrane, particularly those of the laminin family of cell-adhesive proteins. The main receptors for the basement membrane proteins are integrins, a family of more than twenty members with distinct binding specificities. One binds to certain types of laminins and another binds to other laminins or type IV collagen, a basement membrane-specific collagen. All types of epithelial cells need to adhere to the basement membrane to survive, grow, and maintain their differentiated phenotypes.

The basement membrane is not only a substrate for the epithelial cells to adhere to, but also a reservoir for hormones and growth factors, many of which are needed to be assembled in the extracellular matrix to act on target cells. Unlike these soluble factors that interact with cells only transiently, the basement membrane is always in contact with cells and continuously sending signals through the receptors. The cell nucleus always needs some signals or clues about how to activate, and which genes to activate under different situations. Both signals from the basement membrane, and soluble factors need to merge to be effective; if either signal or receptor is denied, the cell starts to die.